Opulence: Performative Wealth and the Failed American Dream

Displayed at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Art, Omaha, NEDecember 9, 2022 - April 16, 2023

This group exhibition assembles a range of creative practices–painting, sculpture, video, fashion, and nail artistry–that embrace lavish, sumptuous aesthetics to examine America’s obsession with wealth and how the ways it is displayed shapes class, race, and gender.

In a capitalist society where ‘good taste’ often signals class affiliations, status, and power; and consumerism peddles materialism as self-realization, marginalized communities are forced to contend with the false promise of the American Dream. By toying with notions of high and low culture, the works in this exhibition employ aesthetics of decadence and wealth to critique how, despite America’s pledge to an equal access to prosperity, systemic barriers deny some communities opportunity and restrict their social mobility.

Artists include Larry Buller, Caitlin Cherry, Max Colby, Yvette Mayorga, Rashaad Newsome, Faleasha Savage, Devan Shimoyama, and Imagine Uhlenbrock.

Back Left: Caitlin Cherry, Swim Lab, 2022. Forground: Max Colby, They Consume Eachother, 2018-2021

1. Queen!

There was a weekly party that came to shape my years living in Chicago. Every Sunday, almost like church, queers, House music stans, and club kids convened for Queen! in the cloistered basement of Smartbar. If I could take the night off from serving tables, I made the two-bus pilgrimage to the North Side club. Anointed by the sweat of my fellow dancers, I found fellowship in the mass of gyrating bodies; communion in inebriation; and reverence in the throbbing hymns of House DJ legends. Queer dancefloors are heralded as an escape from the day-to-day marginalization and objectification that gay and transgender people experience navigating public spaces. This congregation, assembled under the tenets of bodily affirmation and creative expression, was led by drag queens who administered rites, set the vibe, and turnt the party.

Like priests, these queens donned extravagant regalia, served looks, and thus established the terms of the fantasy by which the club and its celebrants operated. The self-proclaimed “International Black Bearded Beauty,” Lucy Stoole was (and continues to be) one of the most celebrated and prominent hostesses of the party, seducing the crowd with lavish garments and an infectious personality. I was too sheepish to approach the queens’ saintly presence, but after one night of hedonistic dancing, as I approached the staircase to ascend back to banal normalcy, I encountered Lucy Stoole descending the stairs like a woke Duchamp painting.1 I was transfixed by Lucy’s stunning makeup, charming smile and opulent outfit.

I greeted her with a timid, eager smile.

I asked for a hug which she graciously gave me.

I walked away aglow with enchantment, and bewitched by her glamor.

I greeted her with a timid, eager smile.

I asked for a hug which she graciously gave me.

I walked away aglow with enchantment, and bewitched by her glamor.

Faleasha Savage is an Omaha-based entertainer and vocal trans rights activist. For Opulence, Savage shares her wardrobe including jewelry, the many crowns and sashes she has won, and a selection of garments many of which she made herself.

Faleasha Savage is an Omaha-based entertainer and vocal trans rights activist. For Opulence, Savage shares her wardrobe including jewelry, the many crowns and sashes she has won, and a selection of garments many of which she made herself. The etymology of “glamor” has roots in the Scottish term gramarye, or magic. Today, notions of glamor still revolve around charm, allure, and mysterious enchantment. Transgender theorist and DJ, Terre Thaemlitz, traces the shifting meaning of glamor observing that “Europe's ruling elite used opulence as an ideological weapon to befuddle the lower classes with glimpses of heaven on earth–a lifestyle so foreign and unattainable that it could only be the result of divination.”2 This historical vignette explains how we arrived at today’s definition of glamor as more closely related to affluence than magic and underscores the social and political leverage won through public displays of wealth.

Lucy Stoole–magicienne, enchantress–had cast a spell of opulence on me.

Faleasha holds holds 5 national titles and over 40, regional, state, city, and bar titles represnted here by her many crowns.

2. A Dream Deferred

The American Dream was inspired by the Declaration of Independence’s assertion of each citizen’s right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The promise: every hard working American has an equal shot at upward mobility and wealth. Early on, this Dream manifested as freedom, land, and opportunity. By the mid 20th century the booming post-WWII economy reintroduced it as a suburban, Leave-it-to-Beaver, white-picket-fence fantasy, binding the American Dream to homeownership. In practice however, even from its conception the Dream never extended beyond white men, leaving Native communities displaced and decimated; enslaved people of African descent economically and socially disenfranchised; women as second class citizens; and queer folx erased.

Today politicians wield the American Dream as a rhetorical weapon, mostly to blame their political opponents for its diminishing viability.3 A study by the World Economic Forum paints a pessimistic picture, illustrating the plummeting potential of Americans to earn more than their parents over the last century4–a hallmark of the American Dream’s success. Meanwhile people of color still suffer the legacy of exclusion, experiencing higher income inequality and lower rates of social mobility than their white counterparts.5

The complex, exclusionary histories that defined the American Dream and how it, in turn, has benefited white men while hobbling women, queer folx, and people of color, has been interrogated by historians, journalists, and scholars. The intentions of this text and exhibition are not to reproduce or justify this scholarship but, instead, to examine the creative modes of resistance that some artists from marginalized communities have employed in the face of the false promises of the American Dream. The artists in this exhibition reclaim agency through self-expression. Their practices interrogate the conflation of success with wealth. And in a capitalist society that peddles materialism as self-realization, they show us how America’s obsession with wealth shapes class, race, and gender.

Yvette Mayorga, Mirror Mirror, 2022; Objects Left Behind, 2019; Tweety Nameplate, 2022; Daydreaming Notes (Wallpaper), 2022.

3. They go high, we go low

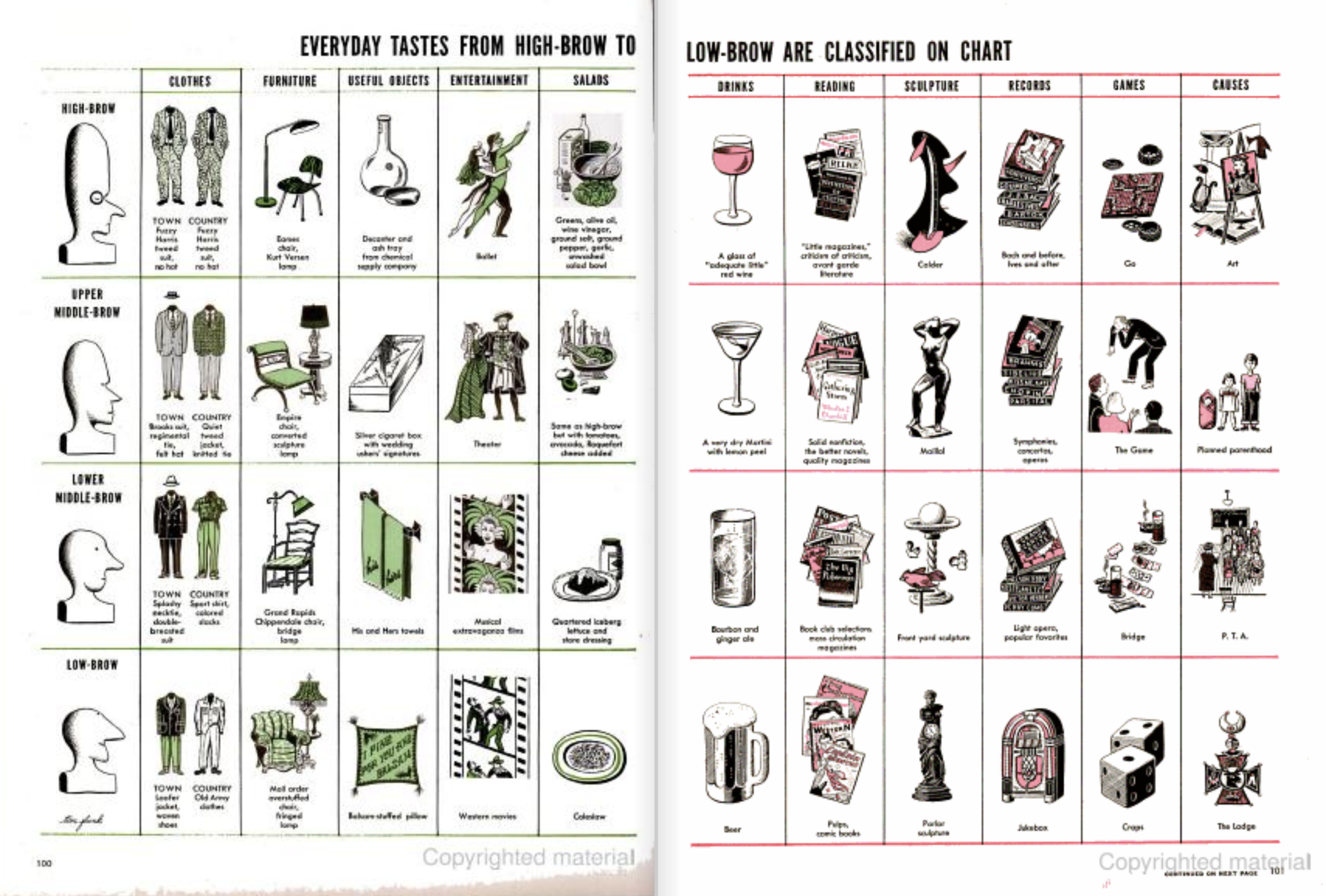

A 1949 issue of Life Magazine offered a chart for readers to locate themselves on the high-brow, low-brow spectrum through their preferences in commercial goods and activities.6 This exemplified America’s obsession with and self-consciousness of taste and class. Decades later French sociologist Pierre Bordieu’s research led him to insist on taste’s class-shaping role. “Art and cultural consumption are predisposed, consciously and deliberately or not, to fulfill a social function of legitimating social differences,” he argued.7 To tag someone as having bad taste is to assert your own, superior taste. Jo Weldon, burlesque performer and author, puts it another way:

There’s usually some kind of class statement explicitly or subtly included; “tacky” is what is too easily accessible to people either without resources or abusive of the resources they have. Tacky, as a concept, refers to the lack of cultivation or resistance to taste, and more often than not refers to tastes that are not suitably conservative.8

A 1949 issue of Life Magazine offered a chart for readers to locate themselves on the high-brow, low-brow spectrum through their preferences in commercial goods and activities.6 This exemplified America’s obsession with and self-consciousness of taste and class. Decades later French sociologist Pierre Bordieu’s research led him to insist on taste’s class-shaping role. “Art and cultural consumption are predisposed, consciously and deliberately or not, to fulfill a social function of legitimating social differences,” he argued.7 To tag someone as having bad taste is to assert your own, superior taste. Jo Weldon, burlesque performer and author, puts it another way:

There’s usually some kind of class statement explicitly or subtly included; “tacky” is what is too easily accessible to people either without resources or abusive of the resources they have. Tacky, as a concept, refers to the lack of cultivation or resistance to taste, and more often than not refers to tastes that are not suitably conservative.8

Russell Lynes, “High-Brow, Low-Brow, Middle-Brow.” Life, April 11, 1949, 100.

Russell Lynes, “High-Brow, Low-Brow, Middle-Brow.” Life, April 11, 1949, 100.

Every artwork in Opulence includes an element of tacky: glitter, glitz, “too much,” or “too explicit.” The artists demonstrate an acute awareness of how hierarchies of taste uphold and affirm class structures by toying with perceptions of high and low culture. Caitlin Cherry renders black strippers and drag queens in kaleidoscopic paintings, a medium historically reserved for subjects of religious significance, political power, or mythic beauty. Larry Buller fuses garniture sets, an 18th century aristocratic design fad and status symbol, with raunchy, gay, kink imagery. Max Colby’s sculptures remix mid-century American interior design fabrics with camp jewelry.

This amalgamation of high and low disregards assumptions about how taste dictates class, status, and power. The artists in Opulence propose new economies of value by embracing materials and aesthetics that dominant culture might dismiss as tacky and, heedless of respectability politics, they build self-affirming worlds and communities based on their own tastes and values.

Larry Buller, China Cabinet Ready, 2022

4. Fantasy of wealth

It’s useful to revisit and expand on glamor’s linguistic roots as a kind of magic or incantation. Magic suggests not only bewitchment and charm but also illusion and trickery. For queer folx and people of color, the transformative properties of opulence and glamor offer alternate, self-imagined realities to the social and economic conditions that impede prospects of upward mobility.

This exhibition is concerned not with wealth itself but the magical illusion of wealth, or, to borrow the exhibition’s subtitle, “performative wealth.” The artists represented in this show draw from their own backgrounds and personal encounters with displays of opulence: the Harlem Ballroom Scene9, Latinx bakery confections, camp and kink, black femmes on social media, to name a few. “Fabulousness imagines what life could be like in the future and yanks that vision to the present. To the now,”10 writes the artist-theorist madison moore, extolling the liberating potential of fashion for queer people of color.

At the heart of Opulence lies the hope of dreaming beyond systemic barriers; the creativity to imagine bounty in the face of oppression and violence; and the audacity to manifest it.

At the heart of Opulence lies the hope of dreaming beyond systemic barriers; the creativity to imagine bounty in the face of oppression and violence; and the audacity to manifest it.

Caitlin Cherry, Delta-V, 2022; Cibola Burn, 2022.

Caitlin Cherry, Delta-V, 2022; Cibola Burn, 2022.

Rashaad Newsome, Build or Destroy, 2021

Footnotes1. When displayed in the New York Armory show in 1913, Marcel Duchamp’s canonical work, Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912, infuriated American audiences but played a part in sparking a modernist revolution throughout the country, cementing Duchamp’s reputation as artistic provocateur.

2. Terra Thaemlitz, “Viva McGlam? Is Transgenderism a Critique of or Capitulation to Opulence-Driven Glamour Models?” http://www.comatonse.com/writings/vivamcglam.html

3. Jazmine Ulloa, “How a Storied Phrase Became a Partisan Battleground.”

The New York Times. August 21, 2022.

4. Marcus Lu, “Is the American Dream Over? Here’s What the Data Says.” World Economic Forum. September 2, 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/09/social-mobility-upwards-decline-usa-us-america-economics/

5. Randall Akee, Maggie R. Jones, Sonya R. Porter, “ Race Matters: Income Shares, Income Inequality, and Income Mobility for All U.S. Races.” National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2017. https://www.nber.org/papers/w23733

6. Russell Lynes, “High-Brow, Low-Brow, Middle-Brow.” Life, April 11, 1949, 100.

7. Pierre Bourdieu. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. (London: Routledge Classics, 1984), 7.

8. Weldon, Jo. “Who Decides What's Tacky Anyway?” Literary Hub, April 2, 2019. https://lithub.com/who-decides-whats-tacky-anyway/.

9. The Ballroom Scene is an African-American and Latino underground LGBTQ+ subculture that originated in New York City in the late 20th Century. Ballroom offers queer and trans people of color safe space to form chosen families and communities and express themselves through fashion and dance.

10. Moore, Madison. Fabulous: The Rise of the Beautiful Eccentric. Yale University Press, 2018. 71.

An Omaha-based nail artist and business owner, Imagine Uhlenbrock designed a functioning pop-up nail salon for this exhibtion.

An Omaha-based nail artist and business owner, Imagine Uhlenbrock designed a functioning pop-up nail salon for this exhibtion.  L: Devan Shimoyama, Chakra Chart II, 2021. R: Larry Buller, China Cabinet Ready, 2022.

L: Devan Shimoyama, Chakra Chart II, 2021. R: Larry Buller, China Cabinet Ready, 2022.

Larry Buller, Ostentatious Garniture Set, 2022

Foreground: Faleasha Savage, Expensive Addiction, 2022. Background: Devan Shimoyama, Spotlight, 2021.

Foreground: Faleasha Savage, Expensive Addiction, 2022. Background: Devan Shimoyama, Spotlight, 2021.

Larry Buller, Toy Assortment, 2022